More than 160 million people speak Russian every day.

But where does it come from?

Did Prince Vladimir really speak Russian 1000 years ago?

Saints Cyril and Methodius supposedly invented the Russian alphabet.

But how did they come up with an alphabet which made everyone say "Great, let's use those letters"?

If Rus was Kievan, why is Russian not the official language?

How did the words "хлеб" (bread) and "беспредел" (disorder) and the letters Ё and Ъ come about?

And, of course, where does Russian swearing come from?

I. Old East Slavic. The Beginning

When are languages born?

When they get their names.

The word "Русь", from which the Russian language got it's name, first appeared no later than 9th century.

This word has a complex history.

In the 10th century it was often used to describe the Scandinavian elite of the Kievan Rus.

Slavs too, but not all of them straight away: even in the 11th century Novogrodians could say that they were travelling to "Русь", when they set out for Kiev or Chernigov.

Nevertheless, at the beginning of the second millennium absolutely all the Slavic peoples could understand each other without the help of a translator.

Not just Novgorodians and Kievans, but also the citizens of Prague and Belgrade.

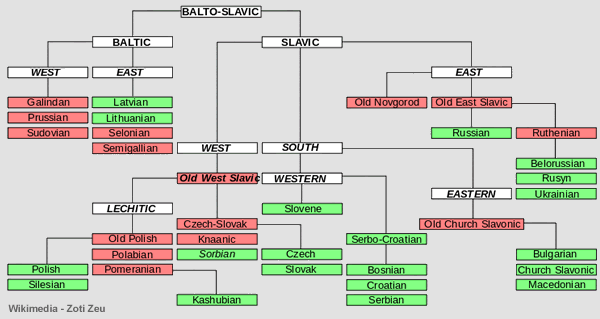

At that point Russian was just a large group of dialects spoken by all Eastern Slavic tribes.

Academics now call this dialect group Old East Slavic, and it is from this group that Ukrainian, Belarusian and Russian all equally derive.

Old East Slavic already had many words that are familiar to us now: "небо" (sky), "наезд" (raid) and "колбаса" (salami), but it was missing such common place words as, "водка" (vodka), "если" (if) или "например" (for example).

Old East Slavic grammar was very different to modern Russian grammar, but traces of it can still be found in modern phrases.

Residents of the Kievan Rus could be called Zhiroslav or Bratoneg.

Whilst the question "Привет, у вас двоих все хорошо?" (Hi, how are you both?)

Would have been something like "Цѣлъвь, съдорова ли еста?" ("Tselyef' sedorova li yesta?")

But what Old East Slavic never had, were any Russian nouns that begin with the letter А.

There weren't any words with the letter Ф (F) either; all of those words are loan words.

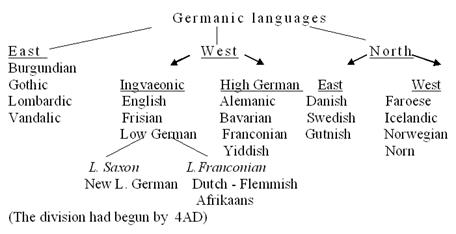

Even at this early point in history there were many words in Old East Slavic that had been borrowed from other languages; from Germanic languages, (letter, banner, anchor, bread, donkey, armour).

Baltic languages, (pot, jug, oakum)

or from Greek, connected to Christianity or everyday life. (lamp, tub, ship, angel)

Some words even came from Latin. (sauna, Greek, marble, bowl, cat)

II. Written Language in the Kievan Rus

It's known that the letters that we use in Russian were invented by the Saints Cyril and Methodius.

However, not everyone realises that they were not Russians themselves, and never even stepped foot in the Kievan Rus.

Cyril and Methodius were two Greek brothers from Byzantium, who, in 9th century, decided to translate the Bible for their Slavic neighbours.

But to do this they needed a written language and literacy.

The brothers studied which sounds Slavs used when they spoke and created letters to match those sounds.

Like these 👇🏼

Russians can't read them today.

That's because Cyril and Methodius didn't create our modern Russian alphabet, but rather the first ever Slavic alphabet.

The Glagolitic Script.

Later on, when it became clear that this new alphabet was overly complex, some of the letters were changed to look closer to Greek ones

This new alphabet was named in honour of Cyril, although it's most likely that the Cyrillic script was invented by the students of the brothers

But letters alone are not enough to translate the Bible.

A language was needed.

One that would be understandable to Slavic readers, but at the same time convey all of the complexities of the bible.

This is also why the Russian translation of the NT is much more accurate than for example the KJV, which I often find atrociously incorrect in all honesty.

Cyril and Methodius created that language, basing it on that Slavic dialect which they had known since their childhood.

Of course, this wasn't the dialect of the far-away Kievan Rus, but rather that of the southern Slavs.

Southern Slavic dialects were understandable for other Slavs, but different.

Where you found "молоко" -moloko- (milk) in the east, you found "млеко" -mleko- in the south.

"Ворота" -vorota- (gates) in the east, was "врата" -vrata- in the south.

"Лодка" -lodka- (boat) in the east, was "ладья" -ladja- in the south.

"ягненок" -agnenok- (lamb) in the east, was "агнец" -agnets- in the south, and so on.

The language which Cyril and Methodius created is known as Old Church Slavonic.

It's important to remember, Old Church Slavonic is not just another name for Old East Slavic; it's part of the same linguistic family but it's still a different language.

Old Church Slavonic played a decisive role in the formation of the Russian language because it became the written language of the Kievan Rus.

During the reign of Prince Vladimir the Great, the Kievan Rus adopted Christianity and its inhabitants started studying the language of holy texts.

The reign of Yaroslavl the Wise saw the creation of the first books written in the lands of the Eastern Slavs.

From this period onwards "Old Church Slavonic" is referred to by academics as just "Church Slavonic".

Educated people had to deal with a kind of double-think; they thought and spoke in one language — their native Russian, but tried to read and write in another — Church Slavonic.

And they didn't always realise that these were two separate languages.

Of course, it was necessary to write about more than just matters of faith.

People needed to chronicle historical events, record laws and write to each other.

The less the genre of a text was related to religious affairs, the more its composition was influenced by everyday spoken Russian.

More than anywhere else evidence of this can be found in the Birch Bark Manuscripts -notes which Eastern Slavs sent to each other 1000 years ago, in order to ask for loans, share important news, or to make confessions of love.

Similar to how we use modern messaging apps.

Church Slavonic lived alongside Russian for so long that it ended up having a huge impact on Russian.

Nowadays we don't realise that such simple words as "овощ" (vegetable) and "власть" (power), "одежда" (clothing) or "время" (time) originally come from this other language.

Without Church Slavonic, Modern Russian wouldn't have half as many compound nouns, like "православие" (Orthodoxy/worship) or "человеколюбие" (humanity/human love), nor would it have participles; we wouldn't be able to say "горящий" (burning) just "горячий" (hot).

III. From Old East Slavic to Russian

Have you ever wondered why the letters Ъ and Ь exist in the modern Russian alphabet despite the fact that they aren't pronouncable?

Or why, up until the October Revolution, Ъ was written at the end of many different words?

The thing is that in Old East Slavic Ъ and Ь (which were called "ер" and "ерь" respectively) were vowels.

Only, unlike other vowels, they were most likely pronounced less clearly.

In the end some usages of the two letters were replaced by other vowels, specifically О and Е, whilst in other places the letters stopped being pronounced altogether.

This linguistic shift changed everything.

Before the shift Russian syllables were open, meaning they ended with vowel sounds.

Afterwards words became shorter and consonants started appearing next to each other in words, changing the way they were pronounced.

The loss of these two vowels split the history of the Russian language in two: before the shift -an ancient and hard to understand language and a language in which it is much easier to recognise the roots of modern Russian.

In the 13th century the Mongols arrived in the Kievan Rus.

Even before their arrival Russians included a considerable number of Turkic words and a couple of mongol origin.

Even the word "орда" (horde) appeared in Russian before the Mongol hordes.

To begin with this word just meant a group of nomads; only later did it come to signify an army.

The Mongols introduced a new portion of turkisms to Russian, primarily related to economics and statecraft.

But one thing that the Mongols didn't introduce was swear words.

The idea of innocent Russians who knew nothing of swearing until the Mongols arrived is a myth.

The roots of Russian swearing are ancient and Slavic.

By the 14th century Old East Slavic was divided into three major linguistic zones, from which formed three different languages.

Of course, there had always been different dialects of Old East Slavic, previously however, the boundaries of those dialects were entirely different.

The dialects of Kiev and Vladimir, for example were much closer to one another than those of Vladimir and Novgorod.

The course of historical events changed all of this.

A part of the Western Slavic lands was integrated into the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and this new political border between Lithuania and Muscovy spawned a new linguistic border.

On one side of this border Ukranian and Belarusian formed, whilst on the other Russian was born.

The Russian language developed from two dialects.

The north-eastern dialects of Moscow, Vladimir and Rostov.

And the north-western dialects of Novgorod and Pskov.

If it weren't for the Novgorodian dialect, it's possible that we wouldn't now say "на руке" (on an arm) but rather "на руце", and not "помоги" (help) but "помози".

On the other hand, if the Novgorodian dialect had completely over-powered the Muscovite dialect, then we wouldn't say "Иван" (Ivan) but "Иване" nor "у сестры" (near [someone's] sister) but rather "у сестре".

At this point Russian begins to leave behind more of its ancient traits.

For example, the complex system of tenses dissappears; now instead of two future tenses and numerous past tenses there is just one of each.

The language also loses the ability to show grammatically that there is not one or many objects but specifically two: dual forms disappear, leaving just singulars and plurals.

In southern and central Rus "a" becomes more widespread, that is, we start pronouncing unstressed "О" vowel sounds as "А", so "молоко" is pronouned as "малако" (malako).

And by the 17th Century the seperate vowel Ѣ (yat), which was pronouced as follows: gradually came, in spoken Russian, to sound the same as the vowel E.

In the 17th Century, Kiev was a centre of education, religion and the Orthodox faith.

It is thanks to the people of Kiev that we pronounce the word "Бог" (God) in the way that we do.

Elements of European culture were imported to the Rus through Kiev, like Polish words, for example.

Polish became the language to know for any enlightened nobleman, or, as they would call themselves, "шляхтичи" (gentleman, from Polish "szlachcic").

From Polish numerous Latin words which were necessary for academic pursuits made their way into Russian.

Until the 18th сentury, Russian people still mostly wrote in Church Slavonic but its position was not as stable as before.

Some talented writers could combine elements of both Russian and Church Slavonic in one text to add stylistic flair.

The students of the first academies in Russia perfectly understood that Church Slavonic was not a more cultured form of Russian, but simply a completely different language.

IV. The Russian Language of a New Age

Peter the Great decided to create a new secular culture in Russia.

He had no need of the aging, Church Slavonic language.

He designed a new civil script which could be used when printing newspapers and scientific publications, and which did away with many unnecessary letters. But not all of them.

Peter ordered that all new books be translated not into Church Slavonic, but into Russian and that all editors remove each and every instance of Church Slavonic words like "еже", "аще" и "егда" from texts.

A new culture brought with it new ideas, for which old words were not enough.

How can go about writing a love letter but the only word close to love in your written language is "похоть" (lust)?

From Peter's time onwards, a wave of loan words poured into Russian.

A new German influence on Russian was added to the prior Polish one.

All of this was part of a new lifestyle; painting, dancing and fencing became the main hobbies of noble youths.

Peter founded the first Russian navy and adopted naval terminology from Dutch and English.

It wasn't just new things which came from the west, but a whole new way of thinking.

After Peter's death it became clear that not everyone wanted to part with Church Slavonic.

Like Lomonosov and Trediakovsky.

They said:

"Church Slavonic is a valuable part of our culture; space has to be found for it."

It made little sense to use Church Slavonic words in everyday speech, but they were very useful for grand, ceremonial works.

For example, for poems glorifying the monarch.

In such texts instead of "город" (city) one should write "град" and instead of "смотри" (look), "воззри".

Towards the end of the century, opponents to this conservative point of view started emerging.

They believed that things should be written as they are said.

Don't write "око" and "чело" if you say "глаз" (eye) and "лоб" (forehead), and if you say "орЁл" (eagle) don't write "орЕл".

For this purpose these opponents would invent the letter Ё.

Two schools of thought formed. (Shishkov and companions vs Karamzin & Co).

For the progressive school the main enemy was words from Church Slavonic.

They considered these words crude rather than grandiose.

For the conservatives however, the enemy was loan words from French.

Instead of "галош" (galoshes), they insisted, one should say "мокроступы" -mokrostupi- (literally wet steppers) and instead of пара (pair), "двоица".

In the end, everybody and nobody won the argument.

Numerous loan words continued to spill into the Russian language, whilst many Church Slavonic words were adapted and took on new meanings.

Before, words like "ангел" (angel), "страсть" (passion) and "прелесть" (charm) were only used in religious contexts but now they could be used to talk about love too.

Thanks to the progressive thinkers we got Pushkin's classic novel "Eugene Onegin" and the slogan

"Православие, самодержавие, народность" (Orthodoxy, Autocracy, Nationalism).

And thanks to the conservatives we got translations of the Bible and the Iliad.

The ideal balance between the ideas of the two schools can be found in Pushkin's works in the 1830s.

Pushkin used a form of Russian which was just as suitable for writing novels and articles as it was for speaking.

Mikhail Lermontov's novel "Hero of our Time" made this style of language mainstream.

But even this style was not always expressive enough.

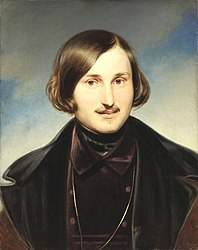

Nikolai Gogol enhanced his linguistic style with popular slang and archaic and dialectal words in order to capture spoken Russian on paper and that was no easy feat given how bizarre his characters were.

After this, Russian literature would split and go down two different overarching paths:

The path of Lermontov and the path of Gogol.

Leskov, Zoshchenko, Remizov / Turgenev, Bunin, Bulgakov

From 18th Century French was the main language of international communication and therefore the main language of the Russian aristocracy.

The Russian officers who took Paris in the Napoleonic wars had such perfect French accents that the Parisians mistook then for fellow Frenchmen.

The writer, Leo Tolstoy, belonged to the golden youth, who were distiguished by their perfect French, as well as by their parents extreme wealth.

Later, he would be extremely ashamed of this.

In the 19th century Russian adopted new words from other European languages mostly terms related to philosophy and politics.

Scientific terminology was so popular that it entered common usage.

By the mid 19th century more and more new social groups began to actively write and speak and undermine the established linguistic norms.

In response, attempts were made to codify these norms.

Throughout the century new academic dictionaries, grammar guides and handbooks on orthography were constantly being published.

Their purpose was to clearly record the meaning of words and to say, "these words are acceptable for newspapers, these ones are for conversations, and these ones are out of date."

That way the language would become more predictable and understandable.

An attempt to add a bit of diversity was made by Vladimir Dal, who added a range of colloquialisms and dialectal words to his dictionary.

His contemporaries didn't aprrove of his work but, after his death, Dal's dictionary became a symbol of the wealth of the Russian language and a source of inspiration for Sergei Yesenin and @AI_Solzhenitsyn.

V. Russian Language in the 20th Century

By the beginning of the 20th century there already existed a single, standardised form of Russian, which was completely destroyed by the revolution.

Newspapers and public squares were taken over by new social groups whose language skills were not the strongest, like the characters of the writer Zoshchenko.

Russian was overrun by abbreviations, new bureaucratic phrases, military terminology, as well as new political and even criminal jargon.

Nevertheless, the Soviet state soon achieved total order, not just in society, but also in language.

As early as 1918 the letters Ѣ (yat) and i, as well as the Ъ which came at the end of many words were removed from the language.

But the final standardisation of Russian orthography came only in 1956.

By then the Ushakov and Ozhegov dictionaries and Rosenthal's handbook had all been published.

These created the new norms on which language should be oriented.

Every announcer on the radio and television spoke identically, the country underwent mass urbanisation, men from different ends of the country served together in the army, and, as a result of all this, Russian dialects began to die out en-masse.

At the same time however, many large cities began to develop new linguistic quirks, and now everyone knows where the people say "батон" and where they say "булка", and where they say "бордюр" and where they say "поребрик".

All Soviet norms were swept away by perestroika.

Just like in reign of Peter the Great, Russian needed new words for its speakers' new lifestyle, so that everyone could talk about business, finances, leisure and sex.

Help was provided by the new international language, English.

In the 90s as in the post-revolutionary period, the linguistic heirarchy of Russian fell apart.

The language of TV annoucners became less sophisticated, swear words were printed freely, and criminal jargon entered the mainstream, being used by even politicians and academics.

In the year 2000 this linguistic chaos began to settle down.

Instead of "секьюрити" -security-, people once again began to say "охранник" (security guard), and new expresions like "эффективный менеджер" (effective manager) became cliches.

At the same time the internet was developing rapidily, helping to spread new words, memes, grammar and spellings at lightning speeds.

Chat rooms broke down the barriers between written and spoken Russian, and social networks gave everyone the ability to get creative with the language.

.jpg)